06 January 2022

DESIGNING HOLISTIC WELL-BEING IN THE AGE OF HYBRID WORKING

Written by Ferdinand Cheung, Director, LWK + PARTNERS

First published on CTBUH Journal 2021 Issue IV

Abstract

The rise of the hybrid mode of working means that people with vastly different backgrounds, knowledge, skills, and individual needs are working alongside and collaborating with each other in the same space. Flexibility has therefore become a key consideration in workplace design, which also coincides with the huge interest in well-being. With these trends in mind, this paper proposes that future workspaces should be “spaces that inspire” the body, mind, and soul. Design recommendations are offered to address well-being from an all-round perspective, benefitting building users, the community, and the environment. The discussion focuses on multi-functionality, bodily health, mental wellness, biophilic environments, community engagement, and responsive workspaces.

Introduction

Never have the modes of work been so diverse in contemporary history. A growing number of multinational employers are transitioning to “hybrid mode” in their daily operations, which is already having an influence on the kinds of workspaces they build for employees.

While coworking spaces are known for their ability to bring individuals of different professions, needs, and work routines together in one place, larger corporations are also becoming increasingly multidisciplinary. Engineering firms are recruiting policy experts, academic research is done across departments, and retail brands are diversifying their product and service offerings to boost market coverage

All this means that people with very different backgrounds, knowledge and skills, and who have varying needs of their own, are working alongside and collaborating with each other in the same space. At the same time, “well-being” is becoming a strong consideration in building design, as people are now hyper-aware of how the conditions of their daily surroundings affect long-term wellness. Meanwhile, employers increasingly recognize that staff well-being is critically linked to business performance and resilience. Ensuring that people work productively in a healthy and inspiring environment, while bringing added value to the community, is now a high priority for both employers and building operators.

Multifunctional, Flexible Neighborhoods

Human well-being is holistic and multidimensional. People spend about a third of their time in their workplaces, and individuals have a range of needs to fulfill throughout the day, in addition to business requirements.

As the boundary between work and lifestyle continues to break down, future office complexes will evolve into efficient, fluid communities where a wide range of spatial functions are within convenient reach of users. These include, but are not limited to flexible workstations, breakout spaces, exhibition venues, arts and performance spaces, healthcare, retail, food and beverage (F&B), sports facilities, greenery, etc.

This mixed-use trend promises not just commercial efficiency, but a joyous and shared culture that encourages a variety of simultaneous social and cultural happenings, generating dynamic energy and a communal experience. The workspace is essentially becoming a multifunction neighborhood, where people gather, dwell, and create with one another, or in their own productive ways.

But simple diversity is not enough. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that, to ensure sustainable business operations, flexibility is equally – if not more – critical as a workplace quality.

The ability to provide flexible work options is also rising as an important attribute for talent retention, especially among the new generation. According to the EY 2021 Work Reimagined Employee Survey, which surveyed more than 16,000 employees from 16 countries across 23 industries, 54 percent of employees would consider leaving their jobs after the pandemic if they are not afforded some form of flexibility in where and when they work, and millennials are twice as likely to quit as baby boomers (EY 2021).

This is echoed by a survey by global management consultancy McKinsey, which reported that nearly three-quarters of 5,000 employees surveyed globally said they would like to work from home for two or more days per week after the pandemic (De Smet et al. 2021).

A sensible curation of amenity-rich mixed-use spaces is a valuable asset that helps companies adapt to a post-pandemic society and retain top talent. Under hybrid working, there will always be part of the workforce working remotely. Facilitating collaboration between those in and out of the office is a challenge, not only for employers, but also designers. Spaces must be designed to accommodate different workstyles, routines and modes of work – private work, face-to-face meetings, virtual conferencing, brainstorming, cross-disciplinary collaborations, knowledge sharing, forum discussions, etc. To elevate the user experience, it remains a task for the architect to link these components seamlessly with walkable circulation systems, interlocking volumes, multilayered greenery, and common areas.

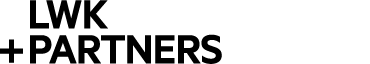

Take Gallium Valley Science Park, our project at LWK + PARTNERS, for example. For this office park located in Cloud Valley in Hangzhou, China, our intention is to surround future users with lots of inspiration, interconnected shared spaces, and social opportunities (see figures 1 and 2). It also aims to improve and enrich the experience of communication and collaboration.

The project consists of laboratories, coworking and meeting spaces, sports facilities, exhibition venues, restaurants and retail outlets, to make up a comprehensive program. A communal “sky-loop” platform on Level 3 connects office spaces with amenities like eateries, roof gardens, and other recreational facilities (see Figure 3).

Taller blocks feature major recesses on building envelopes facing the central courtyard, creating communal terraces to let in fresh air and sunlight into core spaces like lift lobbies and pantries. The project seeks to blur the lines between work, wellness, lifestyle, and the park, potentially becoming a signature type of workspace that fosters a work-life balance in the science-tech industry.

Expanding Focus on Bodily Health

Commitment to staff well-being helps attract talent—a trend amplified by the pandemic—and employers are investing more in it. Even before the pandemic, global advisory Willis Towers Watson found that supporting staff well-being is one of the top four staff benefits priorities for 66 percent of companies globally, and 60 percent in Asia-Pacific (Willis Towers Watson 2019). The latest data from the Global Wellness Institute also reveals that Asia-Pacific employer expenditures on workplace wellness programs/services grew 5.1 percent annually from 2015 to 2017, to US$9.3 billion (GWI 2018).

Research has shown that active office designs have a positive effect on reducing employees’ sitting time (Wallmann-Sperlich et al. 2019). A walkable environment with easy access to greenery and open spaces at different levels and scales encourages people to move around and exercise, while a growing number of office complexes nowadays offer a range of sports and recreational facilities for people to merge their workout routine into their work schedules (see Figure 4).

Addressing well-being is also about creating a space where people feel comfortable to stay for a long time. In an office environment, people can easily be drawn to hours of intense, focused working when assignment deadlines approach, or when workloads grow. Spaces that promote movement throughout the day can make a difference, as physical exercise can stimulate brain activity and speed up task completion. Inserting a feature staircase can be a way to encourage vertical movement, while providing a point of visual attraction. Using desks with adjustable heights allows people to stand up while working, and it also provides an easier setting for group discussion.

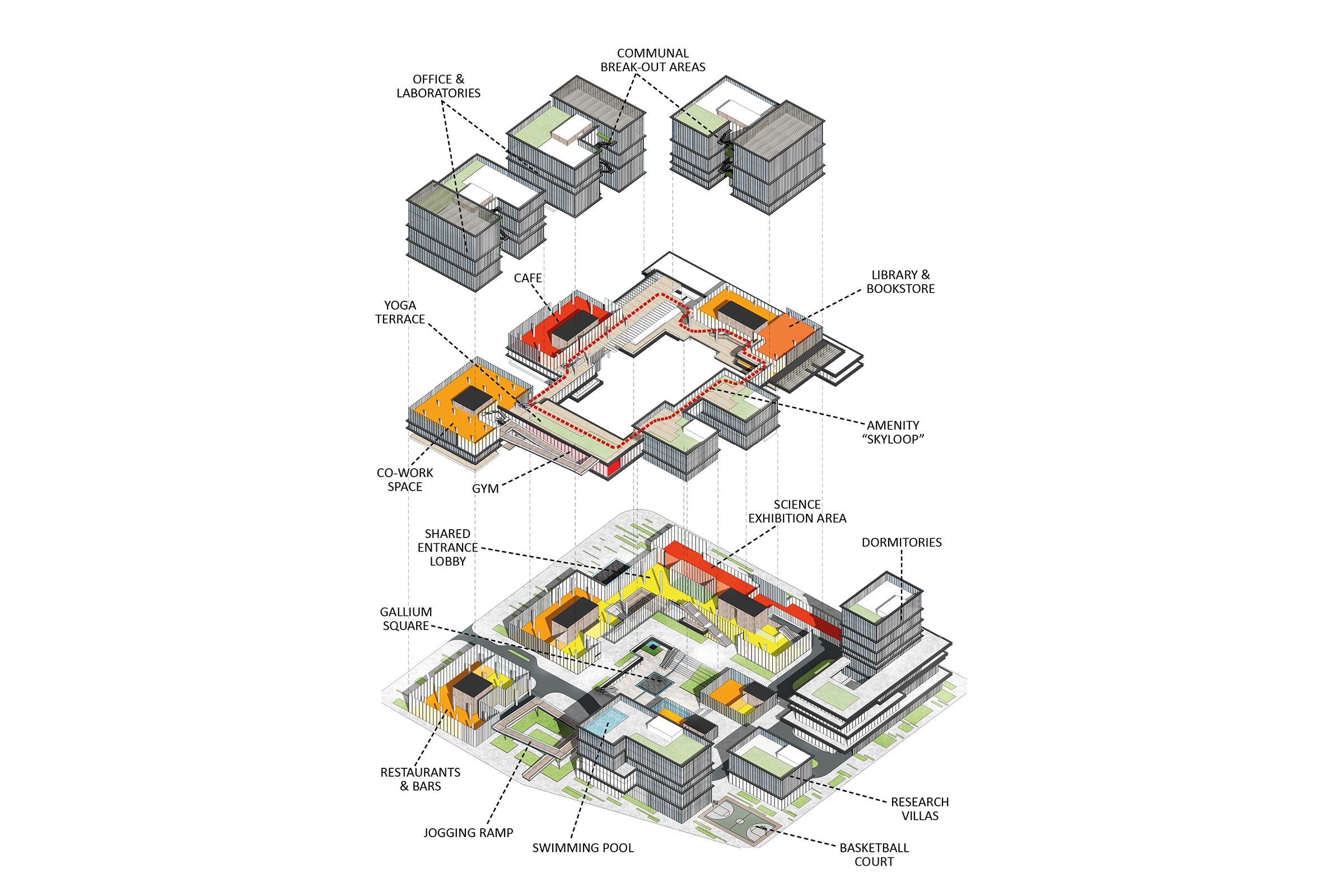

Lighting is an aspect in occupational well-being sometimes overlooked by employers. But the right lighting does enhance people’s performance at work (CBRE 2017). A combination of large openings, skylights, operable windows and passive shading devices all help optimize natural lighting and minimize glare for indoor workers (see Figure 5). Ideally, users can adjust the intensity of lighting, according to the weather and the nature of their task.

Maintaining the right indoor temperature and good ventilation are equally important for safeguarding the well-being of workplace users. Interiors that open out into outdoor terraces, and floor plates cutting into each other can be good ways to draw ample fresh air into the office, while large, visible indoor staircases piercing through the main office space allow air to move from one floor to another. Chilled ceiling systems can also be installed to ensure even distribution of cool air.

Nourishing the Mind, Soul, and Social Self

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that depression and anxiety cost the global economy US$1 trillion per year in lost productivity (WHO 2019), while other studies show that employee satisfaction has a positive effect on performance (Bellet, De Neve & Ward 2019). Workplaces, therefore, should be thoughtfully designed to nourish the mind and soul for workers to keep their brains fresh for the challenges ahead.

Promoting open communications within the team is a long-standing objective in people management. A study reveals that 61 percent of employees in the United States think their productivity at work is affected by their mental health (Mind Share Partners 2019) but a separate survey found only 30 percent of global employees feeling comfortable talking to their manager about their mental health (Segel 2021).

Designing a range of spaces that vary in privacy levels ensures that different kinds of staff engagement activities can take place. While open-plan layouts may convey a sense of spaciousness and transparency, employees also need more secluded booths to voice out their concerns to management in private, undisturbed conversations. Forums, training, and team-building sessions with a larger number of participants can make use of open-air theatres and meeting rooms (see Figure 6).

Experience with nature is definitely part of mental nourishment. Research has shown that different interventions to improve physical and visual access to workplace greenery help reduce human stress levels (Toyoda et al 2020). Therefore, incorporating plantings and greenery has become a mainstream option for 21st-century architecture to provide relaxing breathing spaces for users.

Our team at LWK + PARTNERS took this emphasis on greenery further for Aoti Vanke Centre in Hangzhou, China, with a design that uses the garden as a central driving concept (see figures 7 and 8). As an innovative working hub, the project disrupts the established norm in office architecture that dictates the prime central spot should be occupied by tower lobbies.

Instead, the lobbies take a step back from the forefront , allowing the central courtyard to double as an entry point at the heart of the site, opening up more space to integrate and engage with the urban fabric. Above the courtyard is an elevated podium, each successive level of which rotates by a different degree, reinterpreting the podium-tower typology to create myriad walking spaces for people’s enjoyment.

The project program extends beyond being solely a gathering and social hub for the office workers, but also offers spaces with a distinctive architectural quality. This affords an iconic, dynamic, and sensational moment as one looks up the courtyard, seeing the twisting and shifting of the architecture language of the podium projecting onto the tower. Together with the lush and serene environment secluded away from the noise and the busy city environment, the space also offers a meditative ambiance, giving peace of mind to occupants.

The office should be a place for exchanging ideas and building networks. Casual interactions should be fostered through wide corridors, open terraces, and generous lounge spaces, as peer support and encounters with people help relieve stress. Periods of pandemic-induced isolation and social distancing have highlighted our need to interact and physically share a space with other human beings.

At the same time, the importance of solitude should be recognized. A moment of self-reflection or “me-time” during breaks can be inspirational, therapeutic, and productive. With the rise of “self-care” and growing receptiveness towards a mindful lifestyle, the future workspace should include pockets of quiet spaces, especially in companies where creativity or insight is part of employee output.

Art facilitates serendipity, stimulates different human senses and gives the workspace a unique identity. It inspires a richer ambience, emotions, and encourages dialogue between people moving in the space. This does not necessarily require a large number of artworks, but creating rhythm and movement through architectural forms, depth, and hues can be a promising approach.

Biophilic Design and Communal Well-Being

Office buildings were once developed purely as landmarks of prosperity and development. Today, a more considerate approach would be to harmonize the building with its surrounding landscapes functionally and aesthetically, extending considerations for well-being beyond building users to produce holistic benefits for the community, help people reconnect with nature and minimize disruptions to urban wildlife.

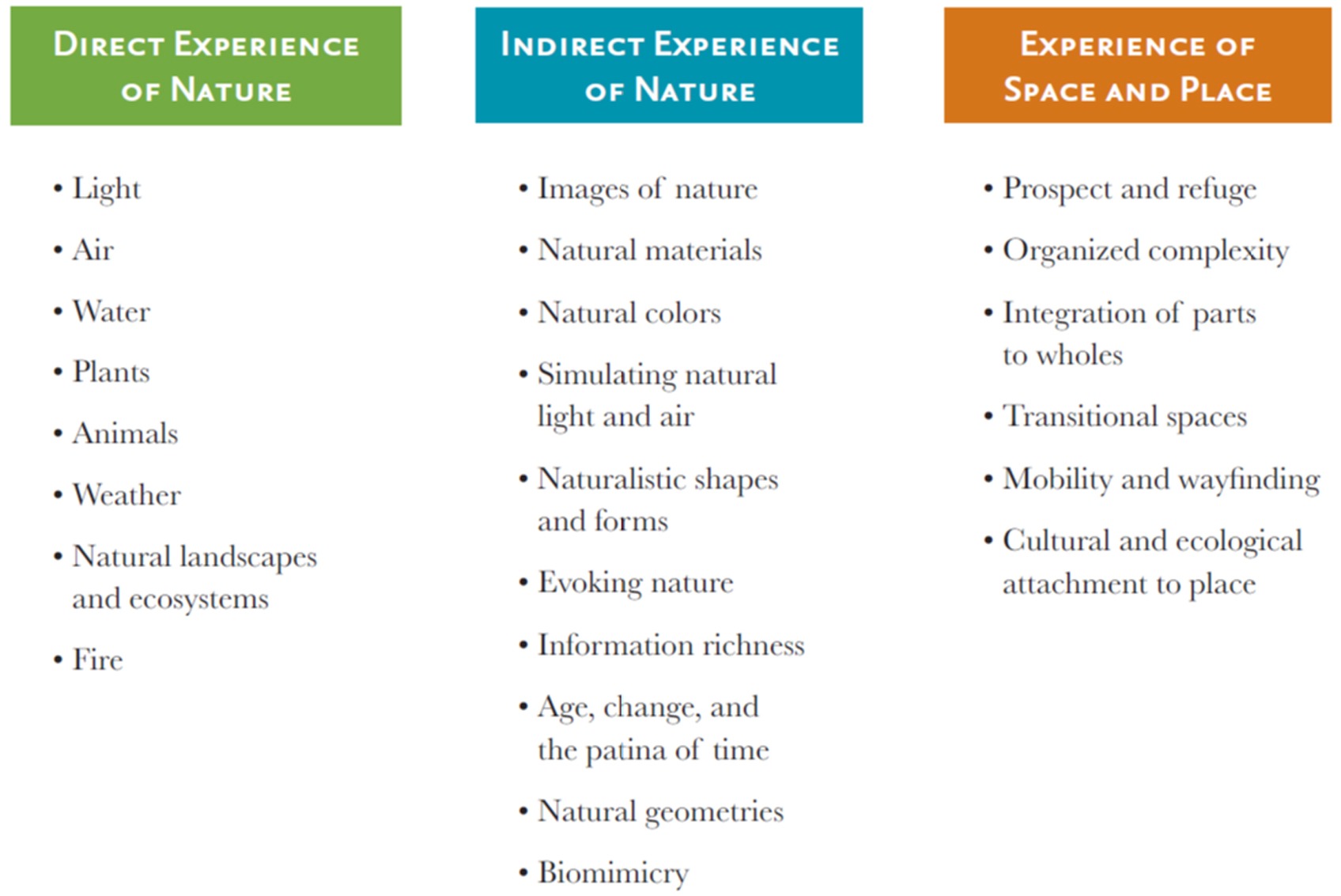

Biophilic design presents a solution that promotes human and environmental well-being, and it is growing as a workplace design trend. Integration of water features, use of non-reflective surfaces, living walls, avoidance of outward-facing bright lights, and prioritizing natural or recycled materials are some of the approaches to creating an eco-friendly development. Kellert and Calabrese (2015) set out a design framework showing three groups of elements contributing to a biophilic experience (see Figure 9).

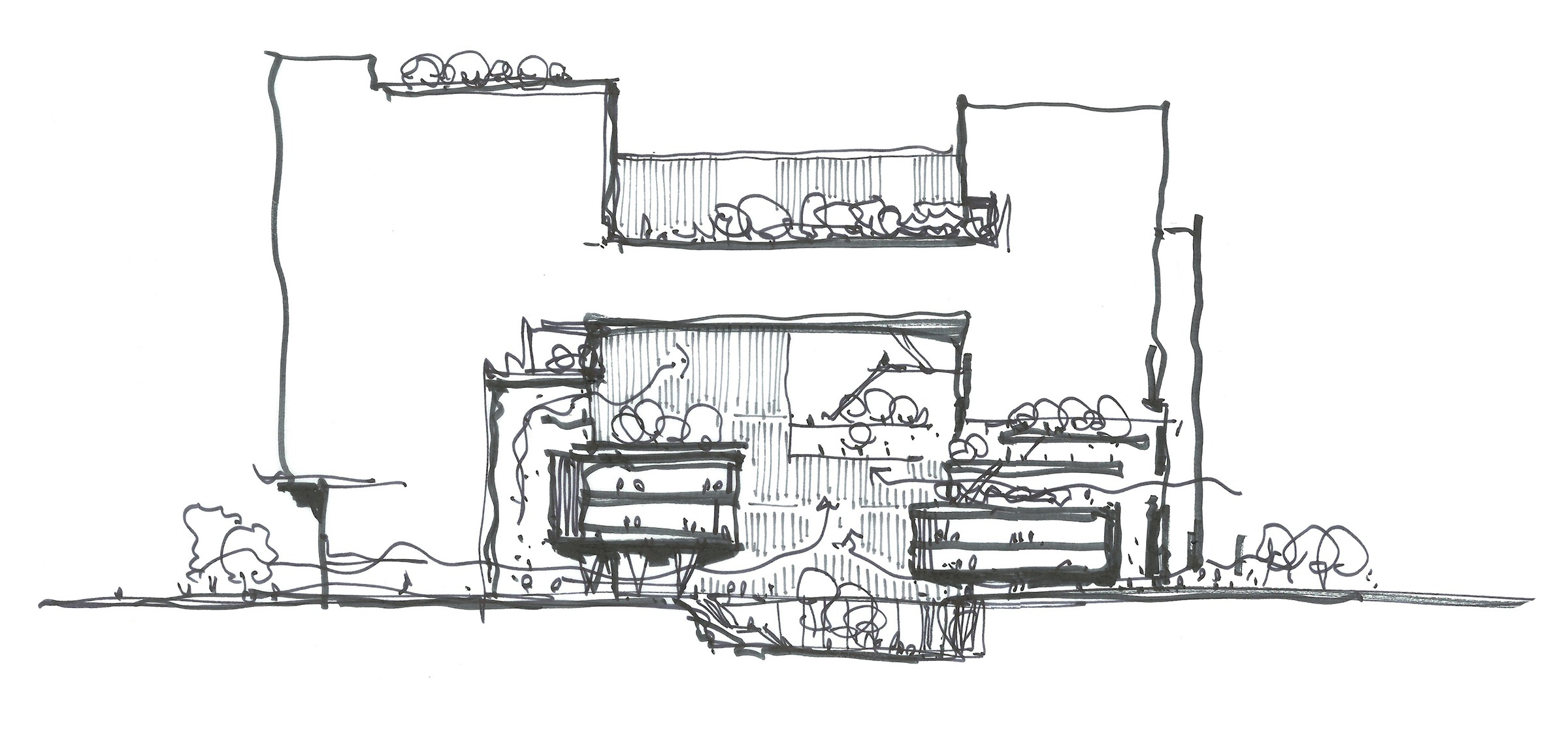

Introducing permeable elements like wind corridors, plant walls, and perforated/louvered façades encourages wind and sunlight to pass through the building. Especially in high-density contexts, this mitigates the “street canyon” effect. Blurring the boundary between outdoors and indoors, more recent commercial developments have come to embrace a new style of building forms, featuring hanging gardens, open-air atria, winter gardens, trees growing through floor penetrations, and more (see Figure 10).

Integration with the physical surroundings can also be expressed in the use of natural forms, earth-tone palettes, rain gardens, and eco-friendly materials like timber, terra cotta, bamboo, and recycled steel.

Taking a step further, there has also been increasing discussion about zero-energy buildings, an emerging typology that produces its own power, with minimal consumption of externally sourced energy.

To create a socially inclusive landscape, the overall community should be included in circulation planning. Rather than restricting the office building to workers, nearby residents can be invited to use and participate in the complex, especially as the workplace evolves into diverse mixed-use programs. Public realms, skygardens, and event venues can be designed for public enjoyment, while integration with the surrounding streetscape brings visual harmony to the neighborhood at large.

As an example, the central courtyard at Aoti Vanke Centre is a very permeable social space (see Figure 11). Connecting two ends of the overall site, it provides a shortcut for people to pass through and integrates with the pedestrian flow in the surrounding streetscape. Members of the public are also encouraged to enter and enjoy the variety of green spaces and retail facilities located around the courtyard.

For another project, the FSH Plaza, a mixed-use development in Nanjing, our team at LWK + PARTNERS goes beyond the considerations of the five-day working week to create an inviting space for community enjoyment (see figures 12 and 13). The project offers two headquarters office blocks, apartments for staff accommodation, and a street with a cultural and family-oriented retail mix, accommodating the family life of employees, people who live or work in the area, and those who may just be visiting.

Responsive Workspaces via the Internet of Things (IoT)

As flexible, hybrid work kicks in, occupancy of the office building will be distributed around the clock as people come to work at different times of the day. With demand for digitalization rising at the same time, energy demand will increase in our future workspaces. Optimizing user experience while pursuing environmentally-sound strategies is a challenge every office architect today must address, to which smart solutions that integrate building information modeling (BIM) will provide much assistance.

In May 2021, Tsinghua University, Vanke, and Microsoft China published the Assessment Standard for Smart Office Buildings, recognized and run by the Chinese Society for Urban Studies, one of the country’s high-level advisory bodies for future sustainable urban development (Microsoft 2021). It sets out 61 measurements for assessing whether an office environment is ergonomic, efficient, and innovative, setting a benchmark for designing and running quality, smart workplaces in China. It measures a space’s ability to enhance health, safety, energy efficiency, carbon reduction, productivity, management efficiency, user satisfaction, and more.

The above academia-industry-government collaboration highlights the extent of interest in the “smart office” in China, which has attracted major participants across public and private sectors.

Smart buildings are most successful when different IoT sensors and building services communicate with and respond to one another, making the building a self-contained ecosystem.

IoT sensors capture real-time environmental data and spatial usage patterns, providing operators with powerful analytics and insights on how to improve future operations and user experiences. The range of data covered by sensors includes temperature, air quality and light levels, water use, space occupancy, movement of people, and more. They also detect security issues, dislocated equipment, and places where a check-up or repair is needed.

The collected data can then be integrated with building management systems (BMSes) to generate adaptive responses within the building, including light switches, air-conditioning, sun shading devices, etc. For example, unnecessary lighting can switch off automatically when no one is around, and weather forecasts from the observatory can be combined with historic space occupancy data to predict optimum energy use and configure building devices.

An effective, responsive environment brings about a well-curated user experience tailored to the needs and habits of different occupants (see Figure 14). It also boosts safety, health, employee satisfaction, resource efficiency, and the quality of building maintenance.

In the longer term, these “self-functioning” smart buildings are critical for helping society transition to a net-zero-carbon future. Currently, buildings account for almost 40 percent of energy-related global carbon emissions (WorldGBC 2020).

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that smart controls and connected devices in buildings could save 230 exajoules (EJ) in cumulative energy savings to 2040, which lowers building energy consumption by 10 percent globally, while enhancing thermal comfort and delivering greater amenities for building occupants (UNEP & IEA 2017).

To bring down global carbon emissions, architects around the world are working to develop “zero-energy” buildings, which generate enough clean energy on-site for their own use, translating into net-zero energy consumption. Combined with government support, digital infrastructure and city planning initiatives, smart buildings are set to transform how we live, paving the way towards the building of smart cities.

Reimagining the Workspace

Not all jobs can be done remotely, and the office as a key workplace, especially for knowledge workers, is likely to persist for some time. At the same time, shifting global work patterns and rising concerns around well-being—trends that have been accelerated and intensified by the pandemic—are fostering new perspectives on what a desirable workplace looks like.

Flexibility is certainly a defining feature for such a desirable workplace. Employers recognize the provision of flexible working, both as a merit point for retaining and attracting high-caliber talent, and as an ingredient for boosting operational resilience at times when global mobility is restricted. This is why the future workspace must be characterized by spatial qualities and design features that allow people to work in the modes that best suit their style.

To engage users in their most productive and creative selves, well-being should be treated as a holistic, integrated concept with multiple dimensions. Designing the future workplace, therefore, also involves the collaboration of ever-more diverse disciplines, especially as the integration of BIM and IoT technologies becomes increasingly important for creating a comfortable, efficient environment for building users.

Growing priorities for a work-life balance have also further dissolved the boundary between the workplace and “third places” for performing our daily life routines. To optimize the user experience, architects will be looking beyond the “functionality” of architecture to achieve spiritual wellness and positive social dynamics.

References

Bellet, C., De Neve, J. & Ward, G. (2019). “Does Employee Happiness Have an Impact on Productivity?” Saïd Business School WP 2019-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3470734.

CBRE. (2017). The Snowball Effect of Healthy Offices. Amsterdam: CBRE.

De Smet, A., Dowling, B., Mysore, M. & Reic, A. (2021). “It’s Time for Leaders to Get Real About Hybrid.” https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/its-time-for-leaders-to-get-real-about-hybrid.

Ernst & Young Global Limited (EY). (2021). “More Than Half of Employees Globally Would Quit Their Jobs If Not Provided Post-Pandemic Flexibility, EY Survey Finds.” https://www.ey.com/en_gl/news/2021/05/more-than-half-of-employees-globally-would-quit-their-jobs-if-not-provided-post-pandemic-flexibility-ey-survey-finds.

Global Wellness Institute (GWI). (2018). Global Wellness Economy Monitor. Miami: GWI.

Kellert, S. & Calabrese, E. (2015). The Practice of Biophilic Design. www.biophilic-design.com.

Microsoft. (2021). “Tsinghua University, Vanke, and Microsoft Jointly Released the First Domestic Assessment Standard for Smart Office Building.” https://news. microsoft.com/zh-cn/清华大学、万科、微软联合发布国内首个《智慧办公建筑评价标准》.

Mind Share Partners. (2019). Mental Health at Work, 2019 Report. https://www.mindsharepartners.org/mentalhealthatworkreport.

Segel, L. H. (2021). “The Priority for Workplaces in the New Normal? Well-Being.” https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/world-economic-forum/davos-agenda/perspectives/the-priority-for-workplaces-in-the-new-normal.

Toyoda, M., Yokota, Y., Barnes, M. & Kaneko, M. (2020).

“Potential of a Small Indoor Plant on the Desk for Reducing Office Workers’ Stress.” HortTechnology 30(1): 55–63. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH04427-19.

UN Environment Programme (UNEP) & International Energy Agency (IEA). (2017). Global Status Report 2017. Paris: UNEP.

Wallmann-Sperlich, B., Hoffmann, S., Salditt, A., Bipp, T. & Froboese, I. (2019). “Moving to an “Active” Biophilic Designed Office Workplace: A Pilot Study about the Effects on Sitting Time and Sitting Habits of Office-Based Workers.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(9): 1559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16091559.

Willis Towers Watson. (2019). “The Evolution of Benefits in Asia Pacific: From Transactional to Transformational.” https://www.willistowerswatson.com/en-ID/Insights/2019/10/the-evolution-of-benefits-in-asia-pacific-from-transactional-to-transformational.

World Green Building Council (WorldGBC). (2020). Sustainable Buildings for Everyone, Everywhere. London: WorldGBC.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). “Mental Health in the Workplace.” https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/mental-health-in-the-workplace.