16 December 2021

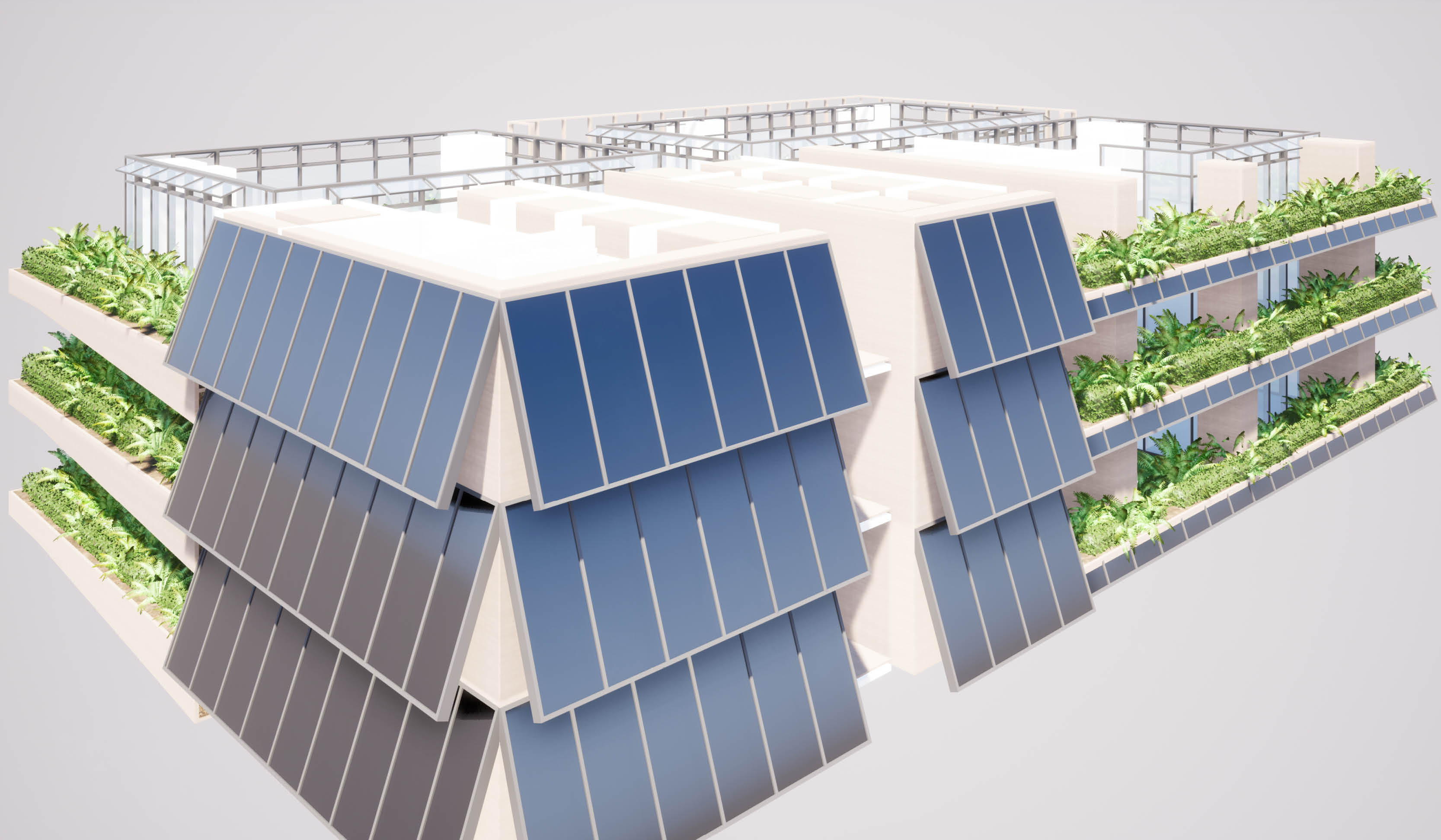

ACT NOW FOR NET ZERO: REMODELLING EXISTING BUILDINGS

Decarbonisation throughout the building life-cycle has become an essence of contemporary architectural design. In Hong Kong, a subtropical high-density city, commercial buildings currently take up the highest percentage of electricity use and this is exacerbated by its ageing building stock which is significantly holding back the city’s transition to carbon neutrality by 2050.

LWK + PARTNERS recently won Merit in the Advancing Net Zero Ideas Competition organised by Hong Kong Green Building Council in Hong Kong with a retrofitting proposal for Oxford House, an existing office building in the city. The design envisions to turn the building into an urban forest paradise, in a high-rise, high-density city context, that promotes mental health and significantly cuts down on energy consumption through active and passive design strategies, bringing the vision of net zero closer to reality.

Innovations to upgrade existing buildings into green, energy-efficient structures have the potential to revolutionise sustainable urban development as it keeps down both embodied carbon (by reusing building materials and avoiding new ones) and operational carbon (by changing how the building operates in the future). As an illustrative example, the Oxford House competition proposal sheds new light on future urban regeneration and helps us rethink the form of future-ready high-rise developments in the age of climate change. Below are the range of passive and active strategies it adopts to achieve low-carbon objectives while maximising users’ thermal comfort and wellbeing.

Minimising heat gain

The first step for lowering energy use in buildings is to reduce heat gain. The Oxford House proposal adapts to Hong Kong’s densely populated humid subtropical urban environment by making the best use of vertical spaces to reduce heat gain from solar radiation and lower the energy demand for cooling.

The proposal reuses and converts the existing façade into a green façade with a setback design that also creates a double-skin façade. It sets back the existing façade while leaving the floor slab extent unchanged, resulting in projecting floors that double as a shading device for the floors below. This reduces the need for new material for building shading.

The setback also creates a double-skin façade, which consists of an external glazing, an intermediate cavity and an inner façade. The external glazing provides protection against weather, while the intermediate cavity, spanning 10 centimetres to 2 metres, would act as a thermal cushion with planters for additional shading and solar absorption. The inner skin protects against indoor thermal losses and facilitates the control of permeability for natural ventilation. The existing low-e external glazing is reused as the inner skin.

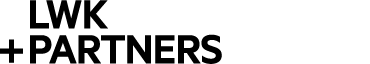

To produce a stack effect, which enhances natural ventilation, voids are opened in existing floor slabs to allow for hot air to move up creating negative pressure to draw the air inside.

Pushing back the line for energy consumption area

Air-conditioning is a major source of energy consumption. Pushing back the line for air-conditioned area is a major sustainable design strategy which involves a combination of natural ventilation and auxiliaries – known as hybrid ventilation.

In this Oxford House example, the ground-floor entrance space is fully opened up to omit air-conditioning altogether. Natural lighting is also introduced to avoid artificial lighting, while a pair of existing escalators is replaced by stair seating to provide both connection between the floors and gathering spaces.

A Green Link is proposed to turn the existing connection into a semi open space for a mentally comfortable atmosphere and to cut down on energy consumption. Cross ventilation is encouraged in common areas like entrances, lobbies and shared corridors, through operable openings and open façades from opposite sides of the building.

These are further assisted by active gears to maximise thermal comfort. A solar chimney is introduced to improve the air ventilation in the car park or foyer. It typically consists of a black-painted chimney which quickly heats up the air inside, creates an updraft of air and draws it to the outside, increasing the air circulation inside the building and cooling the building.

Other energy-saving devices include a combination of big ceiling fans and reflective pools, which improves the thermal sensation of users through water evaporation and ventilation. Post-occupation evaluation can also help determine the optimal level of water-cooled breeze in a semi-controlled environment. Anidolic light pipes are installed to capture daylight and transfer it to indoor spaces, reducing the need for artificial lighting and meaningfully integrate our natural and built environments.

Integration of renewable energy systems

In the future, low-carbon or even zero energy buildings will not only be defined by the amount of energy they save, but also how much clean energy they generate to offset their own consumption.

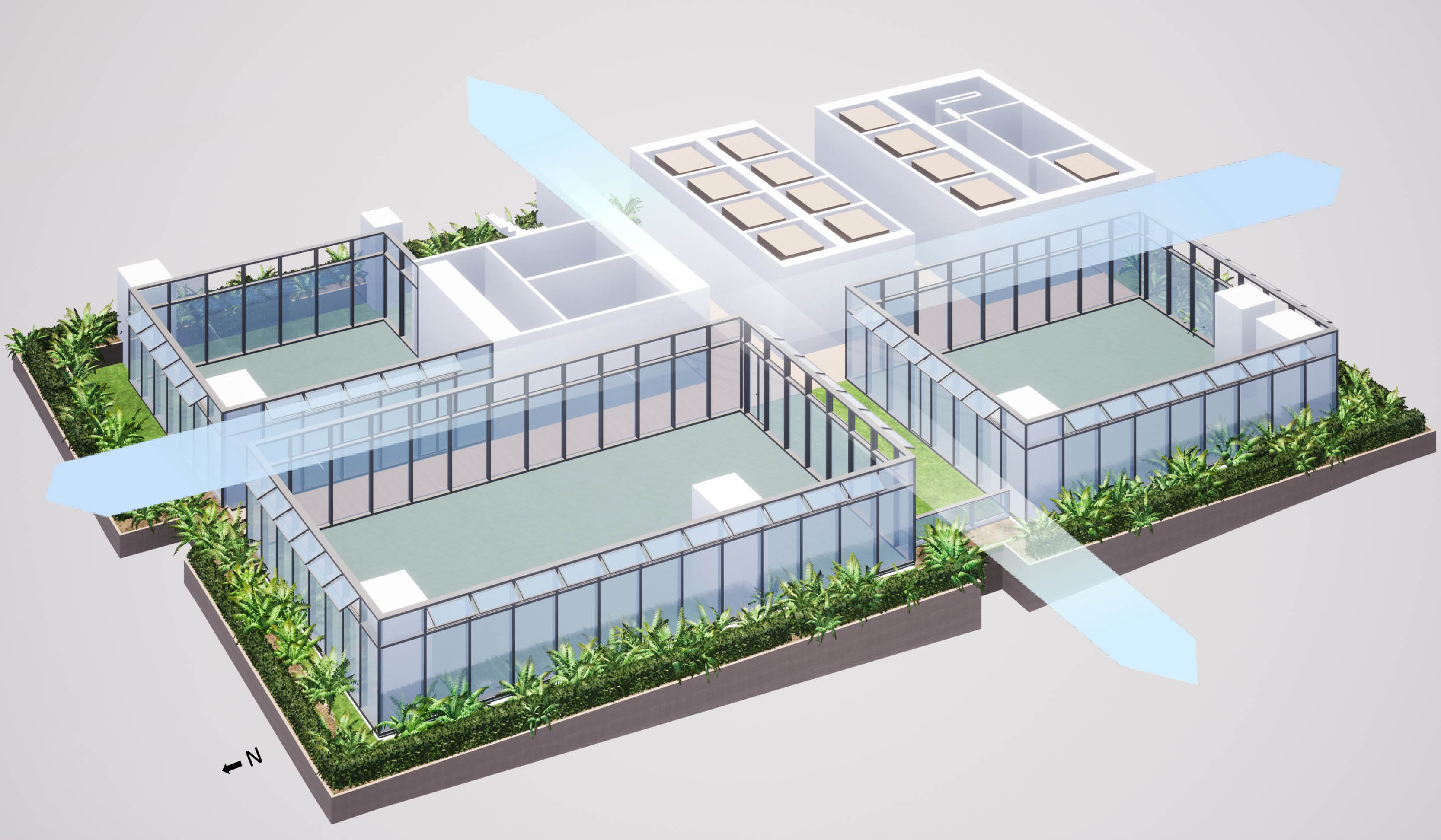

One way is through installing photovoltaics (PV) to generate solar power. The project proposed installing bifacial panels on the rooftop to generate power from both sides of the panels. Due to Hong Kong’s location in the northern hemisphere, panels would face south with a tilt angle to maximise sunlight reception. Panels should ideally be installed on white reflective surfaces for utilising the rears. They also provide shading for the building, lowering the temperature by about 5°C.

Building‐integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV), which means using PV panels as construction materials for the building envelope including the façades, will be used to capture the most sunlight. It is an immediate cut-down on the materials cost and requires minimal care and maintenance compared to conventional materials like tiles and glass, therefore lowering the long-term life-cycle cost.

Solar tiles double as roof tiles and PV panels, with finishes that can mimic the appearance of stone or ceramic tiles. Further installing an insulation layer underneath will reduce approximately 5°C – 8°C in temperature and therefore air-conditioning consumption. For this project, a factory in Guangdong province and a light-weight material are considered to reduce the carbon footprint associated with transportation.

Maximising active carbon conversion

Designing buildings with extensive greenery and landscaping can maximise active carbon conversion. The Oxford House proposal has the existing refuge floor redesigned as a communal sky garden with spectacular views of the Victoria Harbour. The open-sided areas allow cross ventilation to mitigate the heat island effect and enhance the visual permeability of the building. This creates a green urban public space in the fast-paced working environment which blurs the indoor-outdoor boundary and breaks the impression of a traditional business complex with a breathing eco-architecture. A series of green roofs, edge planting and vertical greening will also work as a natural air-filtration system for the health and wellbeing of occupants.

To raise people’s awareness and participation of low-carbon living and waste recycling, the design provides spaces for urban farming, while low-carbon restaurants are conveniently located on all three refuge floors and the roof floor to attract traffic and popularise the concepts of shorter supply chains, less packaging, lower energy consumption and reduction in food waste.

An innovative energy floor system is adopted to allow users to take part in electricity generation through their footsteps as they walk on these special tiles. The energy could be used directly to charge battery packs for smartphones that visitors can use for free in the low-carbon restaurant or light up the energy-efficient LED lighting in the sky garden.

Energy and waste management

Much energy and materials in the daily operation are wasted due to lack of management. The proposal has designed an energy management programme to cut down energy consumption and the amount of waste through recycling, thus reducing carbon emission. It includes the following devices or measures:

• High-efficiency LED lighting

• Solar-adaptive window blinds with automatic shading system

• Regenerative lifts

• AI-based energy optimisation solution (AI-EOS) for HVAC system

• High-volume low-speed fans / displacement ventilation with temperature setback

• Chilled beam system plus raised floor displacement ventilation

To minimise carbon dioxide (CO2) and wastewater emissions, the design features an internal water cycle as a visible design element while improving the climate within the building at the same time. First thing to consider is to reduce water consumption by using low-flush toilettes and dry urinals. Alternatives for fresh water sources are rainwater harvesting and reuse of separated and treated wastewater streams like greywater (wastewater of non‐toilet origin).

Change of mindset and behaviour

Changes in workplace culture and individual behaviours to create the most with the least resources can indeed have a huge impact on carbon reduction. The design encourages the use of open plans, co-working spaces and sharing of workstations as employees may not all be using the office at the same time. This saves 1/3 of working space and prevents duplicated systems and resources.

The proposal also encourages people to walk or cycle to work by providing shower and bicycle parking facilities, which reduces about 10% of CO2 emissions on average. It also promotes the use of staircase instead of lifts by designing more user-friendly, highly visible staircases with wider steps and natural ventilation.

The threat of climate change is imminent, and we need to act fast. Our high-density urban habitats are now packed full of inefficient built structures which are in want of redesign and upgrades. To advance net zero, future architecture must take more heed to remodelling or modifying existing buildings as much as building greener new ones to cut back energy consumption.