21 October 2020

STREETS AS THE IMPETUS OF COMMUNITY LIFE

Fostering a liveable city requires the engagement of various stakeholders. Policy makes up one side of the story, but the participation of residents in placemaking is equally important for achieving urban spaces truly fulfilling for the local people.

How can architects help? How can building design encourage placemaking? LWK + PARTNERS Director HC Chan, with 18 years of project experience and well versed in humanising architecture in dense urban contexts, thinks it’s time that people reconsider the impact of vertical built environments on the quality of life and social dynamics. The streets, he said, are the vessels of colourful history and cultural diversity, and should be preserved as the main site of daily life and a highly walkable environment.

The veins of community life

“A vibrant street scene is an indicator that the community is brimming with life,” said HC. Urban Regeneration in dense cities has often seen a sprawling of vertical spaces, with native community elements reeling from the pressure of Gentrification. The situation has prompted architects like HC to rethink how to keep social networks, history and the urban fabric in place and encourage cultural inheritance by enhancing connections between buildings and the street.

With the street comes people, which naturally makes it the heart of community planning. Besides macro policy, traffic flows are also driven and steered by buildings located on both sides of the avenue. The shops are especially key: “Traditional street-level shops are immensely diverse in scale and type, and together with the kaleidoscopic shop windows, they provide a wide range of visual stimulations and create a unique identity for the neighbourhood.”

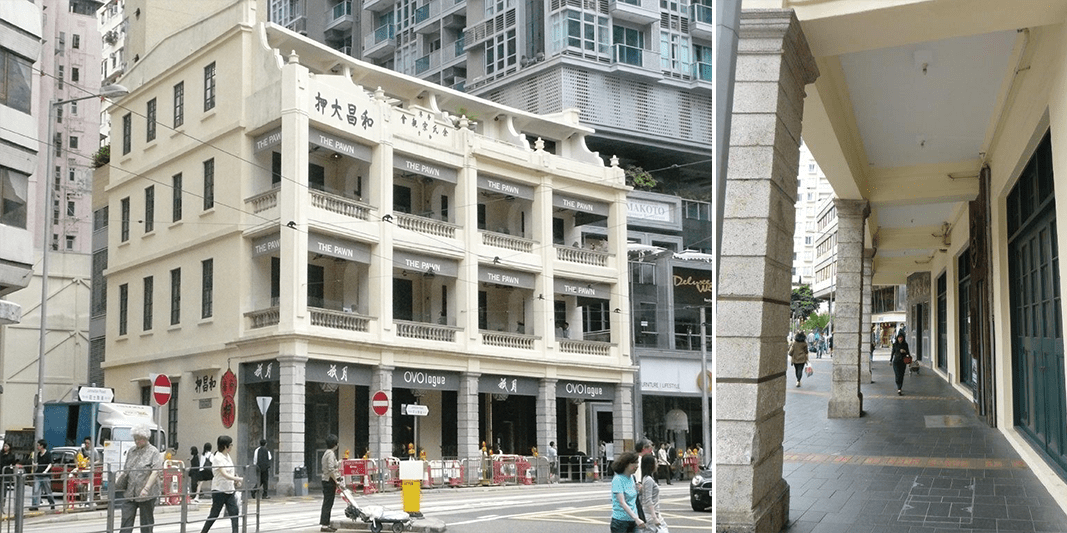

For HC Chan, Hong Kong’s indigenous community planning and vernacular architecture in pre-war era can provide inspiration for newer developments: “Retail colonnades formed by rows of composite buildings built side by side are a signature of old Hong Kong. These ‘weather-protected’ sheltered spaces are where human connections grow, and they provide shades and rest spaces for passers-by. Open-air balconies on the upper levels also allow users of the building to come into direct sensory experiences with the outside world, receiving sunlight, wind and the bustling sounds of life downstairs. It’s a three-dimensional extension of the streetscape. These environmentally sound structures should be brought back to re-humanise our streets.”

Apart from a vivid retail scene, people living near to friendly public spaces are more likely to innovate and collaborate with one another to initiate place-specific urban programmes catering to local needs: “Small changes can bring significant improvements to the overall spatial experience making it easier for the public to come and stay, use or wander. Building shelters over benches, removing any fences around the lawns, replacing staircases with ramps for the convenience of people with disabilities, or improving wayfinding are all beneficial to the community.”

Kai Tak new area as Hong Kong’s next-generation green community

In Hong Kong, for instance, the past 20 years has seen a significant number of commercial podiums topped with high-rise residential towers emerging as a phenomenal typology. Footbridges linking clusters of shopping malls and residential estates have become the key connectivity for people. By contrast, street frontages are mainly occupied by plant rooms where people rarely visit.

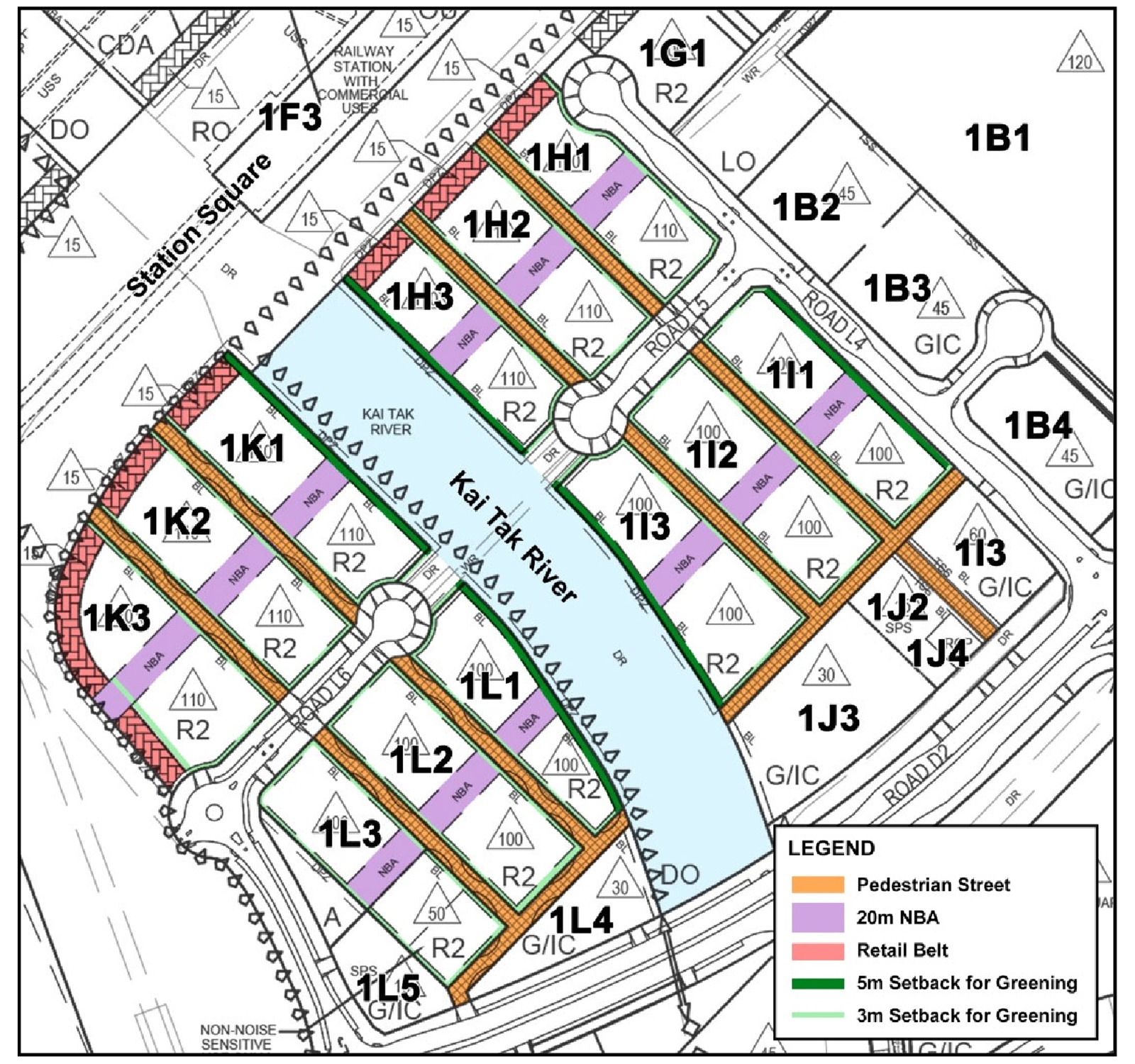

“Public spaces are the core urban connector for society,” said HC, “Streets that are not pedestrian-friendly would become desolate, which is why Hong Kong’s Kai Tak new area takes on an unprecedented planning approach. Buildings are pushed further into the site to open up street spaces to create a new community with life, energy and style.”

Building heights at Kai Tak are controlled to minimise the blocking of views, while site coverage is reduced so that pavements can be broadened. Land lots are planned in grid patterns and buildings are built with certain distances apart to create visual corridors, mitigating street canyon effect and urban heat island effect. Five-metre setbacks are reserved for greening on both sides of the Kai Tak River, which is meandering through the heart of the district, to create additional recreational space for residents. The district is also connected to neighbouring districts through cycling trails to encourage regular exercise.

LWK + PARTNERS plays a pivotal role in giving shape to the emerging Kai Tak new area with nine ongoing or completed projects, including One Kai Tak residences completed in 2018. The practice was architect of the project and HC was in charge: “Tall buildings are arranged to maximise views of the famous Victoria Harbour; and buildings are planned as far apart as possible to provide the most privacy for residents. All these aim to create a green, sustainable and sensible community for all.”

At One Kai Tak, residential blocks are connected with streets, public spaces and transport facilities through retail colonnades and lush landscape. This contributes to the development of a slow mobility system in the area with ample sunlight and fresh air at hand, encouraging residents to get outside into the green. The use of stairs and curves are minimised so that everyone regardless of age or physical conditions can enjoy these pleasant green spaces and take part in community life.

Implications for future retail design

The street may be an excellent source of inspiration for future retail design, but in high-density context where land is scarce, architects must work hard to adapt the street-level experience in inventive ways. How street elements can be brought organically into vertical spaces is a constant challenge to meet rising demands for space while preserving traditional character, social relations and diversity. Buildings that blend well with the streetscape is also more likely to evolve in harmony with the area itself.

To keep the street experience afresh, HC is in support of future shopping malls taking a ‘semi-open’ approach and multidirectional circulation system: “We’ve seen a lot of creativity in recent developments. Large podium volumes have been bisected into smaller-scale cluster blocks in the style of shopping villages. Semi-open interfaces are created with glass curtain walls, transparent canopies and naturally-ventilated corridors. Most circulation takes place on ground level or via interconnected walkways to promote the kind of horizontal, free-flow, boundless navigation experience offered by the street to put on an engaging shopper experience. Further, adoption of green walls and natural materials can promote ventilation and sunlight reception, reducing energy consumption, in line with arising environmental awareness.”

“Buildings are not just objects; they are statements that represent the common values of a society. As architects, our work is not confined to the form of the building, but to use architecture as means to enhancing the overall urban landscape and shaping new ways of living. Through design, we trust that collaboration with developers as well as residents to reinvigorate community life in cities and bring back the long-lost human touch.”