12 April 2021

CONSERVATION OF LINGNAN ANCESTRAL HALLS

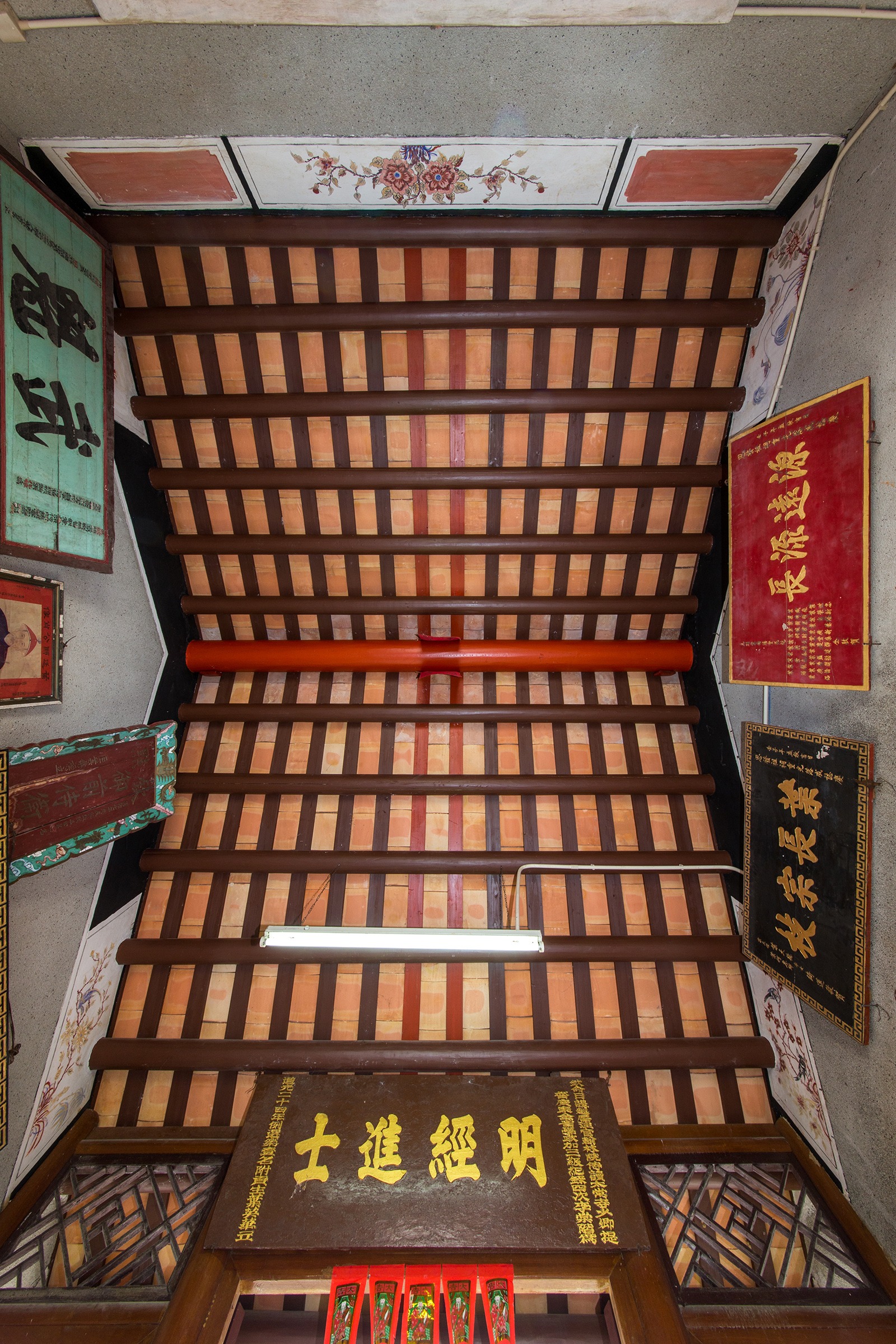

Ancestral halls are the architectural expression of a salient social organisation in traditional Chinese society: kinship. Often standing as the most eye-catching and magnificent structure in older villages, ancestral halls are where all the ancestral tablets are worshipped daily, functioning as the central site for uniting the family. It is also the place for recording glorious feats within the clan and performing rituals during festive occasions. However, as time progresses, continued urbanisation and regeneration programmes have brought these important cultural treasures under immense pressure. Deterioration is fast and the need for conservation is imminent.

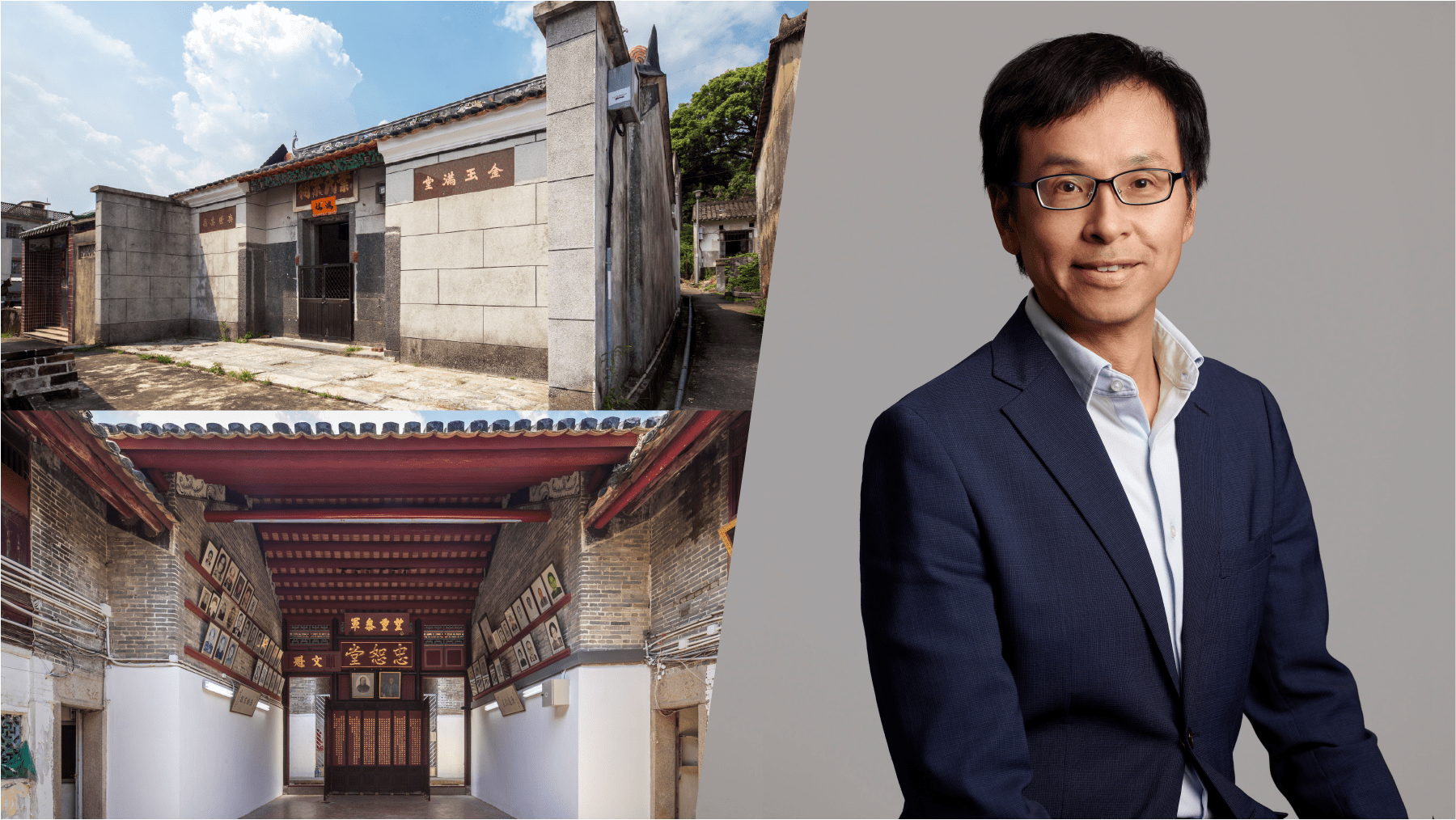

We had a conversation with Eric CM Lee (CM), LWK + PARTNERS Director and head of Heritage Conservation Team with over 20 years working in heritage study and conservation for historic buildings, who shared his extensive experience and insights on restoring Hong Kong’s Lingnan-style ancestral halls.

What is special about the architecture and design requirements of Hong Kong’s ancestral halls?

CM: Ancestral halls reflect the customs and architecture of a place. In Hong Kong, they are mainly divided into local and Hakka styles. Local ones are typically built with two-hall-three-bay layouts with one courtyard, or three-hall-three-bay layouts with two courtyards. For wealthier, more established clans, their buildings are larger and more extensively decorated. By contrast, Hakka ancestral halls are more flexible and dynamic in their layouts, with relatively smaller scale and simple, basic decorations.

Ancestral halls are symmetrically built to show ‘respect for the centre’. The most important spaces are located along the central axis with secondary spaces on both sides, while the left prevails over the right. For building materials, local ancestral halls are mainly built with grey bricks, wood and stone. The façade features grey brick walls and granite columns. As granite was seen as a valuable building material, it was used to draw attention to the façade. The building and materials of Hakka ancestral halls are relatively simple, mainly using grey bricks with rear halls clad in stone walls and rammed earth. Granite is only used in the main door frame.

Ancestral halls are extensively adorned with symbolic wood carvings, murals, plaster mouldings and Shiwan ceramics reflecting the residents’ desire for a better life and cultivating moral ideas. These decorations represent various auspicious and moral concepts. Peony for prosperity, and peach for longevity, for example. Some are homophones – ‘deer’ and ‘heron’ are pronounced like ‘wealth’ while ‘bottle’ resembles ‘peace’ in Cantonese. Some decorations depict stories from Chinese opera, novels and history, with traditional moral concepts in their themes.

What are the challenges of conserving / restoring these ancestral shrines? How to solve these difficulties?

CM: An important principle for restoring ancestral halls or old buildings is to use original building materials, techniques and designs as much as possible. However, since these buildings were built long time ago, some craftsmanship has been lost, and materials have been discontinued, especially with the decorations. For instance, Shiwan ceramics, which are commonly used in ancestral halls, are no longer produced in Hong Kong. We could only hire craftsmen in mainland China and have the works delivered to Hong Kong to be installed if needed. Another example is with the grey brick walls severely damaged by natural erosion, which would need large amounts of the original bricks. Local supply is limited and we had to source them from other villages in the New Territories. Unfortunately, it is complicated to find bricks with the matching size.

Since most ancestral halls have not been properly documented or photographed, we can only make estimations about their original appearance based on oral history and do our best to find original materials as far as possible. We should also be extra cautious about adding new elements. Due to the high maintenance cost and various other reasons, the awareness of protecting historical architecture was weak in conventional society causing the lack of conservation efforts with ancestral halls.

How important is conserving ancestral halls and other historical buildings?

CM: Historical buildings have witnessed the cultural development of a place and are valuable social assets for everyone. Conserving built heritage contributes to a city’s soft power and boost competitiveness. As part of society’s collective memory, historical buildings help people understand their past and cultural identity, reinforcing a sense of belonging among residents. This pushes society forward while creating significant socioeconomic value. Pure economic and urban developments are not enough. Society should take a proactive role to encourage the conservation, care and respect of historical buildings through integrated planning and regulations. In every city, new and old buildings should coexist in harmony, promoting diversity and sustainable development for a unique urban identity.